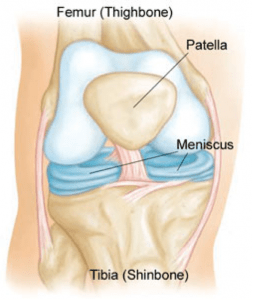

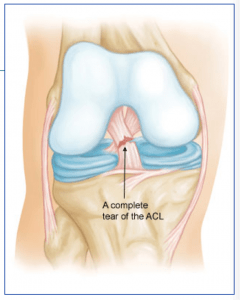

Anatomy: The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) runs from the back of the tibia (lower leg bone) to the front of the femur (thigh bone). It prevents the tibia from sliding backwards, especially when the knee is bent while going down stairs and inclines. Similar to the ACL, the PCL sits in the center of the joint and has poor blood supply that contributes to its poor healing potential.

The PCL is much thicker and stronger than the ACL, but when injured as an isolate injury, the PCL does not lead to as much instability as the ACL. However, often the PCL is injured in high energy accidents, such as motorcycle accidents, and often other ligaments are injured at the same time. With multiple ligament injuries, the combination often results in the knee being unstable for sports or daily activities, so multiple ligament injuries often require surgery to reconstruct the involved ligaments.

Injury Mechanism: The PCL is often injured when the lower leg bone sustains a direct blow from the front while the knee is bent, causing the lower leg bone to be pushed backwards. Occasionally, high-energy sporting injuries cause enough force to tear the PCL or several ligaments of the knee. PCLs can be an isolated injury, but often occur with associated injuries to the meniscus (cartilage pads) or other ligament combinations.

Symptoms: When the PCL or multiple ligaments are torn, usually rapid swelling occurs, usually within the first 24 hours. If multiple ligaments are involved, patients often describe a feeling that they “do not trust the knee.” The following day, one typically describes stiffness, swelling, and pain with weight bearing.

Diagnosis: The physician’s work-up will start with a careful history and exam. Often the description of sustaining a direct blow to the front of the lower leg, or often bruising over the front of the lower leg, can lead the physician to the suspected injury to the PCL. A history of immediate swelling of the knee (effusion) will further lead to this diagnosis. Once the patient can relax the muscles around the knee, the physician can feel the instability on the exam.

X-rays are often obtained to see that no fractures have occurred with the injury and to help assess the overall condition of the knee joint. An MRI scan is often obtained to confirm the diagnosis and to evaluate any associated injuries to the menisci, other ligaments, and damage to the joint surfaces. Plain x-rays show the bones of the knee, while MRI scans reveal the soft tissues around the knee including the ligaments, menisci, muscles and tendons.

Treatment: Your physician will discuss treatment options with you. Treatment decisions are based on age, activity level, degree of instability, and associated injuries to other structures about the knee. An isolated injury to the PCL can often be treated without surgery. The isolated PCL injury does not cause as much “giving way” as an ACL injury.

However, when the PCL is injured, one often develops arthritis in behind the kneecap and on the inside of the knee many years down the road from the original injury. Therefore, in a younger person, one considers reconstructing the PCL, even as an isolated injury, to prevent later arthritis. In an older individual, one can strengthen the muscles around the knee (especially the quadriceps) and expect to have a good long-term outcome from the PCL injury.

Occasionally, bracing can help for high-risk activities and sports. When the PCL is injured in addition to other ligaments in the knee, surgery is often required to re-establish stability in the knee. Surgery involves replacing the torn PCL and possibly the other injured ligaments with another tissue (a graft). Repairing the native PCL does not work, because of the poor blood supply mentioned above, so a substitute tissue must be used for the graft.

Tunnels are drilled in the femur and tibia at the attachment site of the normal PCL. The graft can then be passed through the tunnels to replicate the course of the normal PCL. The graft is fixed at both ends until the graft eventually heals into the tunnels and re-establishes a blood supply. Graft options will be discussed with one’s surgeon, but usually involves taking another tissue from elsewhere around the knee (such as the hamstrings or a portion of the patellar tendon) or taking tissue from a cadaver (another human being).

The cadaver tissue is often recommended because of the larger length and thickness of the PCL to provided an adequate graft. Cadaver tissue is often used for multiple ligament injuries as well because of the lack of enough tissue from ones own tendons to replace all of the damaged ligaments. Risks and benefits of each option will be discussed so a proper choice can be made for each patient.

What to expect after surgery: PCL and often even multiple ligament surgery is now performed as an outpatient procedure. Most patients find that they do best by resting their knee for 3 or 4 days following surgery with protected weight bearing with crutches. As swelling and pain subside, most patients are able to progress their weight bearing rapidly. Once fully weight bearing and not requiring pain medication, the patient can resume driving and returning to office work.

Formal physical therapy begins at one week following surgery and continues once or twice a week for six or eight weeks, depending on each individual’s progress. Patients are using a stationary bike by 3 weeks, and an elliptical or stair climber shortly thereafter. Jogging is restricted until 4 months following surgery and full sports activities are not resumed until 6 months after surgery. Most patients can return to full activities, with no restrictions and no bracing at the 6th month point.

Anatomy

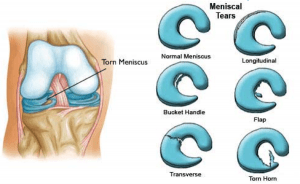

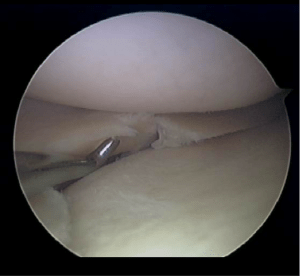

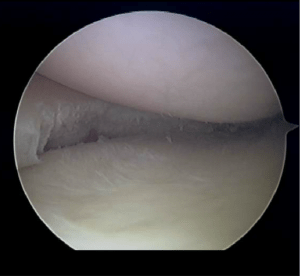

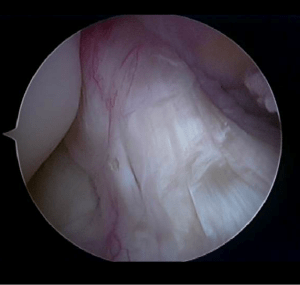

Anatomy The meniscus is often injured with twisting the knee while in a squatting position. This creates a split or flap to occur while the meniscus is being compressed.

The meniscus is often injured with twisting the knee while in a squatting position. This creates a split or flap to occur while the meniscus is being compressed.

Anatomy

Anatomy

What is Cubital Tunnel Syndrome?

What is Cubital Tunnel Syndrome?