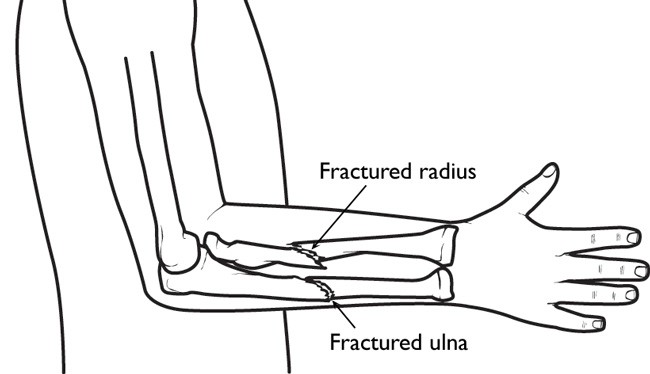

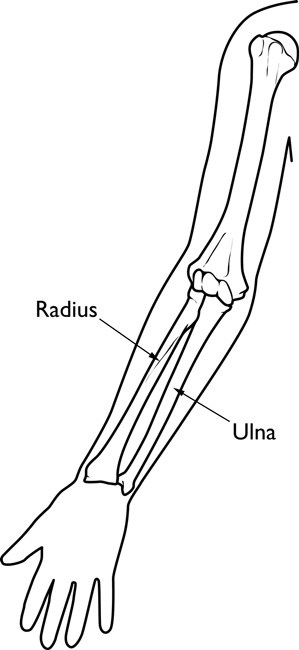

Trying to break a fall by putting your hand out in front of you seems almost instinctive. But the force of the fall could travel up your lower forearm bones and dislocate your elbow. It also could break the smaller bone (radius) in the forearm. The breaks can occur at the wrist (Colles fracture), or near the elbow at the radial “head.”

Radial head fractures are common injuries, occurring in about 20 percent of all acute elbow injuries. They are more frequent in women than in men and occur most often between 30 and 40 years of age. Approximately 10 percent of all elbow dislocations involve a fracture of the radial head. As the upper arm bone slides back into its appropriate place after the dislocation, it can chip off a piece of the radial head, resulting in a fracture.

Signs and symptoms

If you have any of these signs or symptoms after a fall, see your doctor:

- Pain on the outside of the elbow.

- Swelling in the elbow joint.

- Difficulty in bending or straightening the elbow accompanied by pain.

- Inability or difficulty in turning the forearm (palm up to palm down or vice versa).

Fracture types and treatments

Radial head fractures are classified according to the degree of displacement (movement from the normal position).

Type I fractures are generally small, like cracks, and the bone pieces remain fitted together.

- The fracture may not be visible on initial X-rays, but can usually be seen if the X-ray is taken three weeks after the injury.

- Nonsurgical treatment involves using a splint or sling for a few days, followed by early motion.

- If too much motion is attempted too quickly, the bones may shift and become displaced.

Type II fractures are slightly displaced and involve a larger piece of bone.

- If displacement is minimal, splinting for one to two weeks, followed by range of motion exercises, is usually successful.

- Small fragments may be surgically removed.

If the fragment is large and can be fitted back to the bone, the orthopaedic surgeon will first attempt to fix it with pins or screws. If this is not possible, however, the surgeon will remove the broken pieces or the radial head. - For older, less active individuals, the surgeon may simply remove the broken piece, or perhaps the entire radial head.

- The surgeon will also correct any other soft-tissue injury, such as a torn ligament.

Type III fractures have more than three broken pieces of bone, which cannot be fitted back together for healing.

- Usually, there is also significant damage to the joint and ligaments.

- Surgery is always required to remove the broken bits of bone, including the radial head, and repair the soft-tissue damage.

- Early movement to stretch and bend the elbow is necessary to avoid stiffness.

- A prosthesis can be used to prevent deformity if elbow instability is severe.

Even the simplest of fractures will probably result in some loss of extension in the elbow. Also, regardless of the type of fracture or the treatment used, physical therapy will be needed before resuming full activities.