What is replantation?

Replantation refers to the surgical reattachment of a finger, hand, or arm that has been completely cut from a person’s body. The goal of replantation surgery is to give the patient back as much use of the injured area as possible. In some cases, replantation is not possible because the part is too damaged.

If the lost part cannot be reattached, a patient may have to use a prosthesis (a device that substitutes for a missing part of the body). In some cases, a prosthesis may give a person without hands or arms the ability to function.

Replantation is usually recommended when the replanted part will work at least as well as a prosthesis. Generally, a missing hand would not be replanted knowing that it would not work, be painful, or get in the way of everyday life. Before surgery the doctor, if possible, will explain the procedure and how much use is likely to return following replantation. The patient or family member must decide whether that amount of use justifies the long and difficult operation, time in the hospital, and months or years of rehabilitation.

Replantation is usually recommended when the replanted part will work at least as well as a prosthesis. Generally, a missing hand would not be replanted knowing that it would not work, be painful, or get in the way of everyday life. Before surgery the doctor, if possible, will explain the procedure and how much use is likely to return following replantation. The patient or family member must decide whether that amount of use justifies the long and difficult operation, time in the hospital, and months or years of rehabilitation.

How is the procedure done?

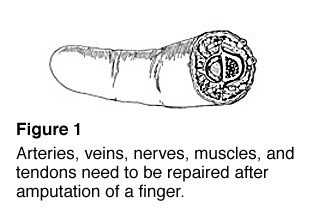

There are a number of steps in the replantation process. First, damaged tissue is carefully removed. Then bone ends are trimmed before they are rejoined. This makes putting together the soft tissue on either side of the wound easier. Arteries, veins, nerves, muscles, and tendons are sewn back together (Figure 1). Areas without skin are covered with skin that has been taken from other areas of the body. Uncovered nerves, tendons, and joints may be covered by a free-tissue transfer, where a piece of tissue is removed from another part of the body, along with its artery and veins.

What kind of recovery can I expect?

The patient has the most important role in the recovery process. Smoking causes poor circulation and may cause loss of blood flow to the replanted part. Allowing the replanted part to hang below heart level may also cause poor circulation. Younger patients have a better chance of their nerves growing back, they may regain more feeling, and may regain more movement in the replanted part.

Generally, the further down the arm the injury occurs, the better the return of use to the patient. Patients who have not injured the joint will get more movement back than those who have. A cleanly cut part usually works better after replantation than one that has been crushed or pulled off.

Recovery of use depends on regrowth of two types of nerves: sensory nerves that let you feel, and motor nerves that tell your muscles to move. Nerves grow about an inch per month. The number of inches from the injury to the tip of a finger gives the minimum number of months after which the patient may be able to feel something with that fingertip. The replanted part never regains 100% of its original use. Most doctors consider 60% to 80% an excellent result. Cold weather can be uncomfortable and a frequent complaint even for those with excellent recovery.

What about therapy and rehabilitation?

Complete healing of the injury and surgical wounds is only the beginning of a long process of rehabilitation. Therapy and temporary bracing are important to the recovery process. From the beginning, braces are used to protect the newly repaired tendons and allow the patient to move the replanted part. Therapy with limited motion helps keep joints from getting stiff, muscles moving, and scar tissue to a minimum.

Even after you have recovered fully, you may find that you cannot do everything you wish to do. Tailor-made devices may help many patients do special activities or hobbies. Talk to your physician or therapist to find out more about such devices. Many replant patients are able to return to the jobs they held before the injury. When this is not possible, patients can seek assistance in selecting a new type of work.

Are emotional problems common following replantation?

Replantation can affect your emotional life as well as your body. When your bandages are removed and you see the replanted part for the first time, you may feel shock, grief, anger, disbelief, or disappointment because the replanted part simply does not look like it did before. Worries about the look of a replanted part and how it will work are common. Talking about these feelings with your doctor often helps you come to terms with the outcome of the replantation.

Your doctor may also ask a counselor to assist with this process. You may find it helpful to talk about it with someone and work through your feelings so you can move on with your life.

Will additional surgery be necessary?

Some patients who have fully recovered from replantation surgery may need surgery later to reach full usage of the part.

Some of the most common procedures are:

- Tenolysis – frees tendons from scar tissue.

- Capsulotomy – releases stiff, locked joints.

- Tendon or muscle transfer – moves tendons or muscles to another spot so that they can work in an area that needs the tendon or muscle more.

- Nerve grafting – replaces a scarred nerve or a gap in the nerves to improve how the nerve works.

- Late amputation – removing the part later because it does not work or has become painful.

Stay in the flow of life. You have many great gifts. Even with the best medical care, you need to be strong during the course of recovery. Remember that quality of life is directly related to your attitude and expectations—not just regaining limb use.

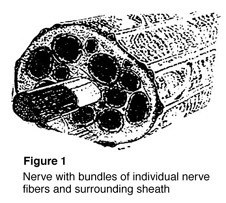

Nerves are the “electrical wiring” system in all people that carry messages from the brain to the rest of the body. A nerve is like an electrical cable wrapped in insulation. A ring of tissue forms a cover to protect the nerve, just like the insulation surrounding an electrical cable (Figure 1).

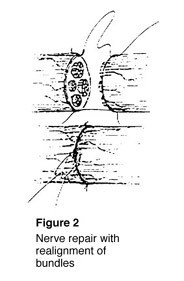

Nerves are the “electrical wiring” system in all people that carry messages from the brain to the rest of the body. A nerve is like an electrical cable wrapped in insulation. A ring of tissue forms a cover to protect the nerve, just like the insulation surrounding an electrical cable (Figure 1). To fix a cut nerve, the insulation around both ends of the nerve are sewn together. The goal in fixing the nerve is to save the cover so that new fibers may heal and work again (Figure 2). If a wound is dirty or crushed, your physician may wait to fix the nerve until the skin has healed.

To fix a cut nerve, the insulation around both ends of the nerve are sewn together. The goal in fixing the nerve is to save the cover so that new fibers may heal and work again (Figure 2). If a wound is dirty or crushed, your physician may wait to fix the nerve until the skin has healed.