Anatomy

Anatomy

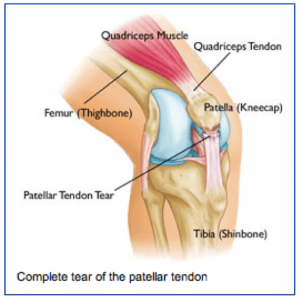

The kneecap (or patella) is a small bone that sits in front of the knee and provides mechanical advantage for our extensor mechanism (quadriceps muscles) in helping one straighten out there knee. The quadriceps tendon attaches to the upper pole of the kneecap and the patellar tendon attaches to the lower pole of the kneecap.

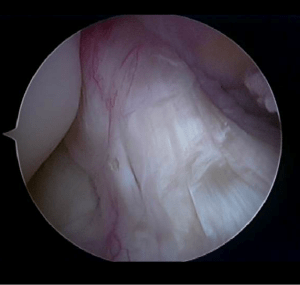

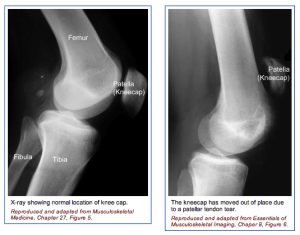

Normally the kneecap glides smoothly in a groove on the front of the femur (thigh bone). The Back of the kneecap and the front of the femoral groove are coated with smooth cartilage that allows the kneecap to glide smoothly.

What is patellofemoral pain?

Patellofemoral pain is a generic term for pain that occurs in the front of the knee. It can result from wearing or arthritis of the joint surface on the back of the kneecap, overuse, malalignment, muscle imbalance, flat feet (pronation) or trauma to the kneecap.

Symptoms

Most patients with patellofemoral pain complain of discomfort in the front of the knee that is worsened with stairs, inclines, sitting for long periods of time, squatting or kneeling, or even with prolonged standing. Occasionally patients report swelling, especially after rigorous activity or episodes in which the patellar has dislocated. Often patients describe grinding (crepitation) when they straighten the knee against resistance.

Diagnosis

The physician’s work-up will start with a careful history and exam. When pain is worse with squatting, kneeling, stairs, and prolonged sitting without a specific injury patellofemoral pain is suspected. The examination often reveals grinding under the kneecap, lateral tracking or malalignment of the kneecap, and often tenderness along either side of the kneecap. X-rays can help determine if the kneecap is tracking properly and if there is any wear starting behind the kneecap. MRI scans are usually not as helpful for patellofemoral pain, except to look for other pathology within the knee.

Treatment

Non-surgical treatment is helpful in the majority of patients with patellofemoral pain. Non-surgical treatment may involve formal physical therapy, cross-training and activity modification, weight loss and general fitness, braces. modification in training schedules and form, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, taping of the kneecap, inserts for shoes, and other modalities. When non-surgical treatment fails, especially with abnormal anatomy (tight lateral restraints or poor alignment), surgery can be helpful.

Sometimes the tight lateral restraints that are tethering the kneecap on one side can be released through the arthroscope (lateral release). In more severe cases in which the kneecap is dislocating or wearing unevenly, more drastic steps are needed to help get the kneecap to track centrally, such as reconstructing the ligament on the inside of the knee or actually cutting the bony attachment of the patellar tendon and moving it to a more central position under the kneecap.

What to expect after surgery

On the rare occasions that surgery is performed for patellofemoral problems, the post-operative treatment depends on the extent of the surgical procedure. If a lateral release is all that is needed, the patient is usually placed in a straight let knee immobilizer for one week while weight bearing fully without crutches. After a week, the brace is removed and therapy is begun to regain motion and strength. It is often 6 to 8 weeks before returning to most normal activities.

If more extensive surgery is needed to re-align the patellar tracking by reconstructing a ligament or moving the bony insertion of the patellar tendon, crutches and bracing may be used initially and the return to full activities may be delayed until complete healing has occurred.

The physician’s work-up will start with a careful history and exam. The physician can often feel the defect in the quadriceps tendon and can appreciate the weakness on trying to straighten out the knee against resistance.

The physician’s work-up will start with a careful history and exam. The physician can often feel the defect in the quadriceps tendon and can appreciate the weakness on trying to straighten out the knee against resistance. Anatomy

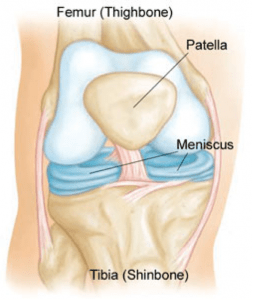

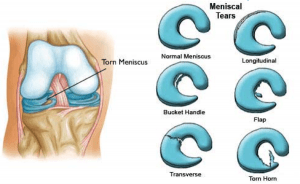

Anatomy The meniscus is often injured with twisting the knee while in a squatting position. This creates a split or flap to occur while the meniscus is being compressed.

The meniscus is often injured with twisting the knee while in a squatting position. This creates a split or flap to occur while the meniscus is being compressed.

Anatomy

Anatomy