Anatomy

Anatomy

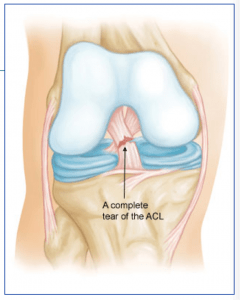

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) runs from the front of the tibia (lower leg bone) to the back of the femur (thigh bone). It prevents the tibia from sliding forward and keeps the knee from pivoting (instability). The ACL sits in the center of the joint and has poor blood supply that contributes to its poor healing potential.

Injury Mechanism

The ACL is often injured in sports with twisting type injuries or hyperextension injuries of the knee. ACL injuries can occur with rapid stopping while running and often as contact injuries. ACLs can be an isolated injury, but often occur with associated injuries to the meniscus (cartilage pads) or other ligament combinations.

Females are known to have a higher rate of ACL injuries than males in the same sports.

Symptoms

The “classic” ACL injury is described as a sudden “giving way” and hearing a “pop” at the time of the injury. Rapid swelling occurs, usually within the first 24 hours.

The following day, one typically describes stiffness, swelling, and pain with weight bearing.

Over the next 1 to 2 weeks, the swelling starts to subside and the range of motion of the knee improves, but patients may start to experience “giving way” or a sense that they cannot trust the knee.

Diagnosis

The physician’s work-up will start with a careful history and exam. Often the description of a sudden “giving way” episode and “pop” can lead the physician to the suspected injury to the ACL. A history of immediate swelling of the knee (effusion) will further lead to this diagnosis.

Once the patient can relax the muscles around the knee, the physician can feel the instability on the exam. X-rays are often obtained to see that no fractures have occurred with the injury and to help assess the overall condition of the knee joint.

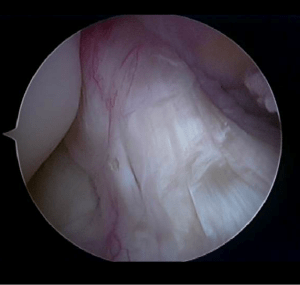

An MRI scan is often obtained to confirm the diagnosis and to evaluate any associated injuries to the menisci, other ligaments, and damage to the joint surfaces. Plain x-rays show the bones of the knee, while MRI scans reveal the soft tissues around the knee including the ligaments, menisci, muscles and tendons.

Treatment

Your physician will discuss treatment options with you. Treatment decisions are based on age, activity level, degree of instability, and associated injuries to other structures about the knee. If a patient is older and does not participate in ACL dependent activities (soccer, basketball, court sports, or other twisting and pivoting sports) the patient may choose nonoperative treatment.

Nonoperative treatment does not mean “no treatment.” The patient is educated about the ACL injury and educated about high-risk activities. Often physical therapy is initiated to help regain full range of motion and strengthen the surrounding muscles that can help stabilize the knee. Occasionally, bracing can help for high-risk activities and sports. If patients in this group have “giving way” episodes after therapy or bracing, they may need to be considered for ACL surgery.

In the younger, more active patients, surgery is undertaken to help stabilize the joint to allow the patient to return to full activities. Surgery involves replacing the torn ACL with another tissue (a graft). Timing of surgery is important.

It has been found best to wait for at least 2 or 3 weeks after the injury before undertaking surgery to give the swelling time to resolve and to allow the patient to recover most of their range of motion before surgery. The chance of developing stiffness following surgery is decreased with better motion going into surgery.

Repairing the native ACL does not work, because of the poor blood supply mentioned above to the ACL, so a substitute tissue must be used for the graft. Tunnels are drilled in the femur and tibia at the attachment site of the normal ACL. The graft can then be passed through the tunnels to replicate the course of the normal ACL. The graft is fixed at both ends until the graft eventually heals into the tunnels and re-establishes a blood supply.

Graft options will be discussed with one’s surgeon, but usually involves taking another tissue from elsewhere around the knee (such as the hamstrings or a portion of the patellar tendon) or taking tissue from a cadaver (another human being). Risks and benefits of each option will be discussed so a proper choice can be made for each patient.

What to expect after surgery

ACL surgery is now performed as an outpatient procedure. Most patients find that they do best by resting their knee for 3 or 4 days following surgery with protected weight bearing with crutches. As swelling and pain subside, most patients are able to progress their weight bearing rapidly.

Once fully weight bearing and not requiring pain medication, the patient can resume driving and returning to office work. Formal physical therapy begins at one week following surgery and continues once or twice a week for six or eight weeks, depending on each individual’s progress.

Patients are using a stationary bike by 3 weeks, and an elliptical or stair climber shortly thereafter. Jogging is restricted until 4 months following surgery and full sports activities are not resumed until 6 months after surgery. Most patients can return to full activities, with no restrictions and no bracing at the 6th month point. Please see the complete ACL physical therapy protocol.