From orthoinfo.aaos.org

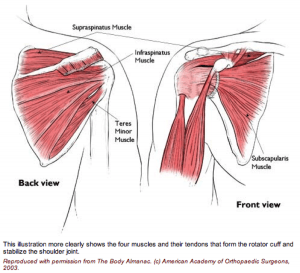

The rotator cuff is made up of 4 muscles surrounding the shoulder.

Three muscles on the back of the shoulder (supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor) converge as a tendon to insert on the outer edge of the humeral head.

They act to elevate and externally rotate the shoulder. The fourth muscle (subscapularis) is on the front of the shoulder and helps internally rotate the shoulder.

Injury Mechanism

Rotator cuff tears can occur after an acute injury such as a fall or catching a heavy falling object, or they can occur over time as a gradual wearing of a hole in the rotator cuff from ongoing rubbing on the acromion such as overuse with overhead or throwing sports.

Symptoms

With acute complete tears of the rotator cuff, patients often describe a burning or tearing sensation at the time of injury. Early along, it is difficult to raise the arm overhead. Patients describe pain and weakness. The pain is usually located over the outer (lateral) aspect of the upper arm. Rotator cuff tears are often painful at night. Older patients may not recall an injury, but may just describe a gradual aching in the shoulder that has progressed over several months or years.

Diagnosis

The physician’s work-up will start with a careful history and exam.

X-rays are often obtained to see that no fractures have occurred with the injury and to help assess the overall condition of the shoulder joint. An MRI scan is often obtained to confirm the diagnosis and to evaluate any associated injuries to the labrum, rotator cuff or damage to the joint surfaces. Often the radiologist will inject contrast into the shoulder joint with a small needle to coat the undersurface of the rotator cuff and to see if the contrast leaks through the rotator cuff suggesting a complete tear. An MRI with contrast is called an arthro/MRI.

Plain x-rays show the bones of the shoulder, while MRI scans reveal the soft tissues around the shoulder including the labrum (lip of cartilage around the socket) and the rotator cuff tendons.

Treatment

Your physician will discuss treatment options with you. Treatment decisions are based on age, activity level and the severity of symptoms. In older patients with less activity demands and less severe symptoms, one will usually start with non-operative treatment including rest, ice, anti-inflammatories, stretching and occasional injections to see if the symptoms become tolerable.

In younger, more active patients, surgery is almost always recommended when a full thickness rotator cuff tear has occurred, since the rotator cuff has poor blood supply, therefore poor healing potential. Rotator cuff surgery is usually done on an outpatient basis. In most cases, the orthopedist will start with an exam under anesthesia to see that full motion of the shoulder is present and to see that the joint is stable. Next, one usually looks into the joint with a small arthroscope (a small lens and camera) so the surgeon can see and probe all of the structures in the joint. Once the complete rotator cuff tear is confirmed, the torn tendon is repaired back to the bony attachment site.

Because there is poor blood supply at the attachment site to the bone, one usually creates a small groove in the bone and pulls sutures through drill holes or uses anchors in the bone for fixation.

What to expect after surgery

Rotator cuff surgery is performed as an outpatient procedure. The surgery takes about 60 minutes. Patients go home in a sling that they use for 3 or 4 weeks. Most patients are uncomfortable for the first 2 or 3 days, but prescription medication is used to help alleviate the pain. Patients are seen back in the office one week after surgery to check their incisions and to start their exercise routine.

For the first 4 to 6 weeks, patients avoid any active elevation of their arm or lifting with that arm. At that point, formal physical therapy is started to improve range of motion and strength. It takes about 3 months from surgery before most of the strength and use of the shoulder returns. Full recovery may take 4 to 6 months.