Description

Osteoarthritis occurs when the cartilage surface of the elbow is damaged or becomes worn. This can happen because of a previous injury such as elbow dislocation or fracture. It may occur due to degeneration of the joint cartilage from age. Osteoarthritis usually affects the weightbearing joints, such as the hip and knee. The elbow is one of the least affected joints due to its well matched joint surfaces and strong stabilizing ligaments. This makes the joint able to tolerate large forces across it without becoming unstable.

A doctor can usually diagnose elbow arthritis based upon a patient’s symptoms and standard X-rays (Figure 1). X-rays show the arthritic changes. Most of the time, advanced imaging studies such as CT (computed tomography) or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scans are not needed. Elbow osteoarthritis that occurs without previous injury is more common in men than women. It usually begins after age 50, although some patients can have symptoms earlier.

Risk Factors/Prevention

Risk Factors/Prevention

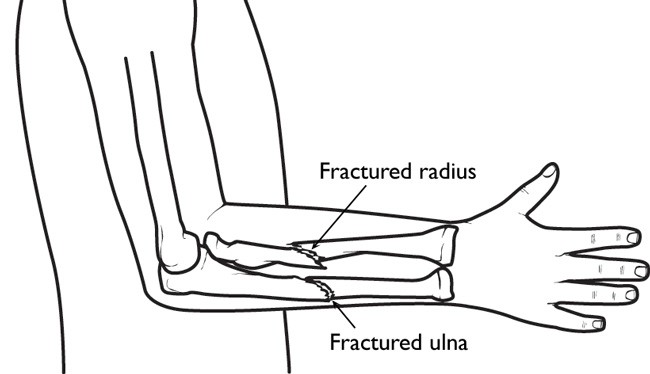

Most patients who are diagnosed with elbow osteoarthritis have a history of injury to the elbow, such as a fracture that involved the surface of the joint, or an elbow dislocation.

The risk for elbow arthritis increases if:

- The patient needed surgery to repair the injury or reconstruct the joint

- There is loss of joint cartilage

- The joint surface cannot be repaired or reconstructed to its pre-injury level

Injury to the ligaments resulting in an unstable elbow can also lead to arthritis, even if the elbow surface is not damaged. That’s because the normal forces across the elbow are altered, causing the joint to wear out more rapidly.

Sometimes there is no single injury. Work or outside activities may also lead to elbow arthritis if the patient places more demands on the joint than it can bear.

For example, professional baseball pitchers place unusually high demands on their throwing elbows. This can lead to failure of the stabilizing ligaments. It usually needs surgical reconstruction. High shear forces placed across the joint can lead to cartilage breakdown over a period of years.

The best way to prevent elbow arthritis is to avoid injury to the joint. When injury does happen, it is important to recognize it right away and get treatment. Individuals involved in heavy work or sports activities should maintain muscular strength around the elbow. Always use proper conditioning and technique.

Symptoms

The most common symptoms of elbow arthritis are:

- Pain

- Loss of range of motion

You might not have both symptoms at once. Patients usually complain of a “grating” or “locking” sensation in the elbow. The “grating” is due to loss of the normal smooth joint surface. This is caused by cartilage damage or wear. The “locking” is caused by loose pieces of cartilage or bone. These can dislodge from the joint and become trapped between the moving joint surfaces, blocking motion.

Joint swelling may also occur. But this does not usually happen at first. Swelling occurs later, as the disease progresses.

In later stages, patients might also notice numbness in their ring finger and small finger. This can be caused by elbow swelling or limited range of motion in the joint. The “funny bone” (ulnar nerve) is located in a tight tunnel behind the inner (medial) side of the elbow. Swelling in the elbow joint can put increased pressure on the nerve. This causes tingling. If the elbow cannot be moved through its normal range of motion, it may stiffen into a position where it is bent (flexion). This can also cause pressure around the nerve to increase.

Treatment Options

Treatment options depend on the stage of the disease, prior history, what the patient desires, overall medical condition, and the results of X-rays.

For the early stages, the most common treatment is non-surgical. This includes oral medications such as Tylenol® or Advil®, physical therapy, activity modification and joint injections.

Sometimes corticosteroid injections are used to treat arthritis symptoms. Steroid medication has typically been used with good results. The affects are temporary. But injections may give significant relief until symptoms progress enough to need additional treatment. An alternative to steroids has been the injection of hyaluronic acid in various forms. This attempts to increase the fluid in a joint, a process called viscosupplementation. It surrounds the diseased cartilage with a thicker and more “cushioned” environment.

This treatment has been recently studied in people with osteoarthritis of the knee. While there was enthusiasm for this treatment, research has not shown it to be better than traditional steroid injections. Additionally, the hyaluronic injections were significantly more expensive. The results of these “viscosupplementation” injections in the elbow or other joints have not been investigated.

When nonsurgical interventions are not enough to control symptoms, surgery may be needed.

Treatment Options: Surgical

By the time arthritis can be seen on X-rays, there has been significant wear or damage to the joint surfaces. If the wear or damage is limited, arthroscopy can offer a minimally invasive surgical treatment. It may be an option for patients with earlier stages of arthritis.

Arthroscopy has been shown to provide symptom improvement at least in the short term. It involves removing any loose bodies or inflammatory/degenerative tissue in the joint. It also attempts to smooth out irregular surfaces. Multiple small incisions are used to complete the surgery. It can be performed as an outpatient procedure. The recovery is reasonably rapid.

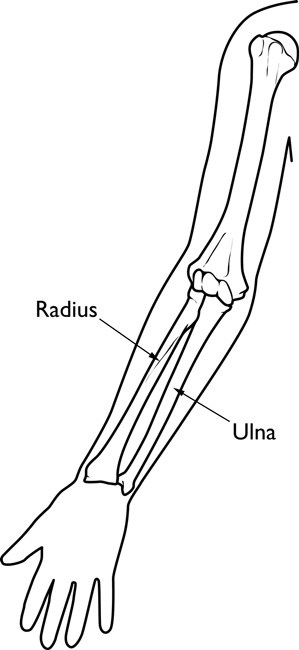

If the joint surface has worn away completely it is unlikely that anything other than a joint replacement would bring about relief. There are several different types of joint replacement available (Figure 2).

In appropriately selected patients, the improvement in pain and function can be dramatic. With an experienced surgeon, the results of elbow replacement are the same as the results of hip replacement and knee replacement. For patients who are too young or who are too active to have prosthetic joint replacement, there are other reasonably good options.

In appropriately selected patients, the improvement in pain and function can be dramatic. With an experienced surgeon, the results of elbow replacement are the same as the results of hip replacement and knee replacement. For patients who are too young or who are too active to have prosthetic joint replacement, there are other reasonably good options.

If loss of motion is the primary symptom, the surgeon can release the contracture and smooth out the joint surface. At times, a new surface made from the patient’s own body tissues can be made. These procedures can give years of symptom improvement.

Research on the Horizon/What’s New?

Recently, joint supplementation has been used as an alternative to traditional oral and injectable medication. For oral medication, this involves a glucosamine/chondroitin supplement. These “nutraceuticals” attempt to give the body more of the basic elements that make up cartilage. Then the body may attempt to maintain or “build back” cartilage. There have been few well-controlled research studies on glucosamine/chondroitin. They have not included patients with elbow arthritis. So the short and long term effects are not yet known. Anecdotal reports have been favorable.

In cases where there has been loss or damage to areas of the joint, a cartilage/bone graft can be considered. This procedure attempts to return the joint to its prior smooth appearance and form in an attempt to prevent further deterioration of the joint. As our understanding of cartilage growth and regeneration improves, this may allow replacement of larger areas of joint damage or degeneration. Newer elbow replacements have also been designed with the goals of greater longevity and easier insertion compared with prior designs.

Risk Factors/Prevention

Risk Factors/Prevention  In appropriately selected patients, the improvement in pain and function can be dramatic. With an experienced surgeon, the results of elbow replacement are the same as the results of hip replacement and knee replacement. For patients who are too young or who are too active to have prosthetic joint replacement, there are other reasonably good options.

In appropriately selected patients, the improvement in pain and function can be dramatic. With an experienced surgeon, the results of elbow replacement are the same as the results of hip replacement and knee replacement. For patients who are too young or who are too active to have prosthetic joint replacement, there are other reasonably good options.