Anatomy

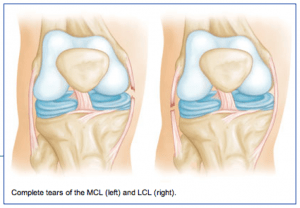

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) runs from the inner side (medial side) of the femur (thigh bone) to the inner (medial side) of the tibia (lower leg bone). It prevents the knee from opening on the inside when struck from the outside of the knee joint. The MCL lies on the outside of the joint capsule and has a good blood supply that contributes to its good healing potential.

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) runs from the inner side (medial side) of the femur (thigh bone) to the inner (medial side) of the tibia (lower leg bone). It prevents the knee from opening on the inside when struck from the outside of the knee joint. The MCL lies on the outside of the joint capsule and has a good blood supply that contributes to its good healing potential.

The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) runs from the outer side (lateral side) of the femur (thigh bone) to the top of the fibula (the smaller of the two lower leg bones). It prevents the knee from opening on the outer side when struck from the inner side of the knee joint. The LCL is thinner and when completely disrupted often requires surgical repair.

Injury Mechanism

The MCL is often injured in sports when one is struck from the outer or lateral side of the knee, such as having an opponent fall against the outside of one’s knee in football. Another common mechanism of injury to the MCL is when the foot is forced out to the side away from the body, such as with a simultaneous kick of a soccer ball with the inside of the foot. LCL injuries are much more rare and usually occur when the knee is struck from the inside while the foot is planted, forcing a distraction force to the outside of the knee.

Symptoms

When patients sustain an injury to the collateral ligaments they often experience pain, localized swelling and bruising on the involved side of the knee. With partial tears, there is stiffness and pain when fully bending the knee, but no sense of instability. With a complete tear, the knee will feel unstable and will give way to the side with any lateral movements.

Diagnosis

The physician’s work-up will start with a careful history and exam. Often the description of a direct blow to either side of the knee can lead the physician to the suspected injury to the MCL or ACL. On examination, the physician can feel the instability when pulling the foot to one side or the other while stabilizing the knee. X-rays are often obtained to see that no fractures have occurred. Occasionally, a small avulsion fracture might hint that a collateral ligament injury has occurred. An MRI scan is often obtained to confirm the diagnosis and to evaluate any associated injuries to the menisci, other ligaments, and damage to the joint surfaces.

Treatment

Your physician will discuss treatment options with you. Treatment decisions are based on degree of instability. Minor tears (sprains) can be treated with rest, ice, elevation and compression. More significant tears in which many of the fibers of the ligament have been torn may require bracing for 6 weeks to keep the fibers from healing in a stretched out position. Occasionally physical therapy is needed to help regain full range of motion and strengthen the surrounding muscles after the period of bracing. Rarely is surgery recommended for an isolated MCL tear, but occasionally LCL injuries can benefit from surgical repair or reconstruction.

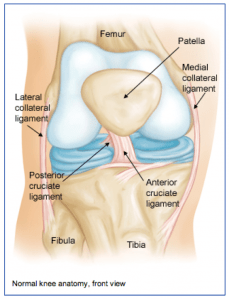

The knee joint is one of the largest joints in the body. It is a complex joint with four bones: the femur (thigh bone), the tibia (main lower leg bone), the fibula (smaller lower leg bone), and the patella (kneecap). The bones are connected with four main ligaments: ACL (anterior cruciate ligament), PCL (posterior cruciate ligament), MCL (medial collateral ligament), and the LCL (lateral collateral ligament).

The knee joint is one of the largest joints in the body. It is a complex joint with four bones: the femur (thigh bone), the tibia (main lower leg bone), the fibula (smaller lower leg bone), and the patella (kneecap). The bones are connected with four main ligaments: ACL (anterior cruciate ligament), PCL (posterior cruciate ligament), MCL (medial collateral ligament), and the LCL (lateral collateral ligament).

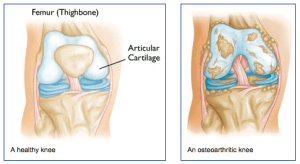

What is arthritis of the knee?

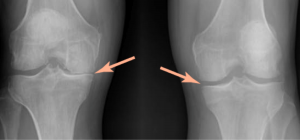

What is arthritis of the knee? The physician’s work-up will start with a careful history and exam. A history of prior injury, pain, stiffness and swelling may suggest arthritis. The exam often shows some swelling and decreased range of motion. Sometimes, patients develop deformities if one side of the knee wears out more than the other side.

The physician’s work-up will start with a careful history and exam. A history of prior injury, pain, stiffness and swelling may suggest arthritis. The exam often shows some swelling and decreased range of motion. Sometimes, patients develop deformities if one side of the knee wears out more than the other side.  Diagnosis

Diagnosis