Dr. Peterson and Dr. Shapiro have been performing a relatively new procedure called reverse total shoulder replacement for the last several years.

This particular procedure is designed for people who have rotator cuff arthropathy or a large, irreparable rotator cuff tear. The rotator cuff is a group of muscles and tendons that surround the shoulder joint and allow you to lift your arm over your head. When this structure is severely torn, shoulder arthritis can set in and mobility is limited.

During this procedure, the surgeon removes damaged bone joint tissue. A smooth, polished, spherical alloy metal “glenosphere” is then fixed to the old bony “cup” of the shoulder, and a stemmed alloy and polymer cup to the shaft of the upper-arm bone.

Why is Reverse Total Shoulder Replacement Done?

This surgery was developed because traditional shoulder surgeries do not work well when patients also have a severe rotator cuff tear with arthritis. With reverse total shoulder replacement, the deltoid muscle powers the new prosthesis, allowing pain free motion overhead in many patients.

Who is a Candidate for Surgery?

Reverse total shoulder replacement may be recommended if you have:

- A completely torn rotator cuff that cannot be repaired.

- Cuff tear arthropathy (arthritis with a severe cuff tear).

- A previous should replacement that was unsuccessful.

- Severe shoulder pain and difficulty lifting your arm.

- Tried other treatments that have not relieved your shoulder pain.

Reverse shoulder replacement may not be recommended for people who have:

- Poor general health and may not tolerate anesthesia and surgery well.

- An active infection or are at risk for infection.

- Severe weakness of or damage to the deltoid muscle of the shoulder.

- A shoulder problem deemed appropriate for more traditional replacement procedures.

How do I Prepare for this Procedure?

Anesthesia – This procedure can be performed under general or regional anesthesia, depending on what your orthopedic surgeon prefers.

Antibiotics – You will probably be prescribed antibiotics to take before and after the surgery to prevent infection.

Medications – Be sure you tell your orthopedic specialists about all the medications you are taking. He may advise you to stop certain medications before the procedure.

Home Planning – There are some things you should be aware of that will make your recovery period much easier. First of all, you will need to take several weeks off from work following the surgery. When you come home, you will need help for a few weeks with dressing, bathing, and simple household chores. Also, you may not be permitted to drive following the surgery and for a few weeks.

What Happens During the Surgery?

A reverse total shoulder replacement usually takes about 1.5 hours. The surgeon will make an incision at the top or front of your shoulder and remove the damaged bone. Then he will position the new components to restore function to your shoulder joint. The incision will then be closed with sutures.What Should I Expect After the Procedure?

After your procedure, the healthcare professionals will give you pain medication to keep you comfortable and several doses of antibiotics. Most patients are allowed to eat solid food and get out of bed the day after the surgery. You will go home on the first or second day following your procedure.

When you leave the surgical center, your arm will be in a sling to provide support. Your orthopedic specialist will instruct you on exercises to increase your mobility and endurance and plan a physical therapy program to strengthen your shoulder and improve your flexibility. Full recovery from this surgery usually occurs in 4-6 months.

The result of our OPEN MRI is a sophisticated diagnostic picture of the area your orthopedic specialist wishes to view. What’s more, there is no pain, no known side effects, and no radiation used with our OPEN MRI.

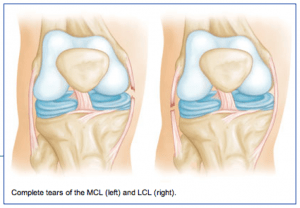

The result of our OPEN MRI is a sophisticated diagnostic picture of the area your orthopedic specialist wishes to view. What’s more, there is no pain, no known side effects, and no radiation used with our OPEN MRI.  The medial collateral ligament (MCL) runs from the inner side (medial side) of the femur (thigh bone) to the inner (medial side) of the tibia (lower leg bone). It prevents the knee from opening on the inside when struck from the outside of the knee joint. The MCL lies on the outside of the joint capsule and has a good blood supply that contributes to its good healing potential.

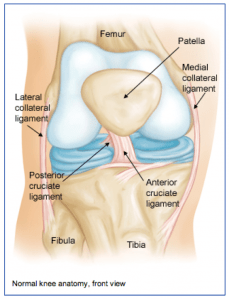

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) runs from the inner side (medial side) of the femur (thigh bone) to the inner (medial side) of the tibia (lower leg bone). It prevents the knee from opening on the inside when struck from the outside of the knee joint. The MCL lies on the outside of the joint capsule and has a good blood supply that contributes to its good healing potential.  The knee joint is one of the largest joints in the body. It is a complex joint with four bones: the femur (thigh bone), the tibia (main lower leg bone), the fibula (smaller lower leg bone), and the patella (kneecap). The bones are connected with four main ligaments: ACL (anterior cruciate ligament), PCL (posterior cruciate ligament), MCL (medial collateral ligament), and the LCL (lateral collateral ligament).

The knee joint is one of the largest joints in the body. It is a complex joint with four bones: the femur (thigh bone), the tibia (main lower leg bone), the fibula (smaller lower leg bone), and the patella (kneecap). The bones are connected with four main ligaments: ACL (anterior cruciate ligament), PCL (posterior cruciate ligament), MCL (medial collateral ligament), and the LCL (lateral collateral ligament).