Arthritis is a condition that irritates or destroys a joint. Although there are several types of arthritis, the one that most often affects the joint at the base of the thumb (the basal joint) is osteoarthritis (degenerative or “wear-and-tear” arthritis).

Osteoarthritis occurs when the smooth cartilage that covers the ends of the bones begins to wear away. Cartilage enables the bones to glide easily in the joint; without it, bones rub against each other, causing friction and damage to the bones and the joint.

The joint at the base of the thumb, near the wrist and at the fleshy part of the thumb, enables the thumb to swivel, pivot, and pinch so that you can grip things in your hand. Arthritis of the base of the thumb is more common in women than in men, and usually occurs after age 40.

Prior fractures or other injuries to the joint may increase the likelihood of developing this condition.

Symptoms

- Pain with activities that involve gripping or pinching, such as turning a key, opening a door, or snapping your fingers.

- Swelling and tenderness at the base of the thumb.

- An aching discomfort after prolonged use.

- Loss of strength in gripping or pinching activities.

- An enlarged, “out-of-joint” appearance.

- Development of a bony prominence or bump over the joint.

- Limited motion.

Diagnosis

Your physician will ask you about your symptoms, any prior injury, pain patterns, or activities that aggravate the condition. The physical examination may show tenderness or swelling at the base of the thumb.

One of the tests used during the examination involves holding the joint firmly while moving the thumb. If pain or a gritty feeling results, or if a grinding sound (crepitus) can be heard, the bones are rubbing directly against each other.

An X-ray may show deterioration of the joint as well as any bone spurs or calcium deposits that have developed.

Many people with arthritis at the base of the thumb also have symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome, so your physician may check for that as well.

Treatment

In its early stages, arthritis at the base of the thumb will respond to nonsurgical treatment.

- Ice the joint for five to fifteen minutes several times a day.

- Take an anti-inflammatory medication such as aspirin or ibuprofen to help reduce inflammation and swelling

- Wear a supportive splint to limit the movement of the thumb, and allow the joint to rest and heal. The splint may protect both the wrist and the thumb.

- It may be worn overnight or intermittently during the day.

Because arthritis is a progressive, degenerative disease, the condition may worsen over time. The next phase in treatment involves a steroid solution injection into the joint. This will usually provide relief for several months. However, these injections cannot be repeated indefinitely.

Surgical Options

When conservative treatment is no longer effective, surgery is an option. The operation can be performed on an outpatient basis, and several different procedures can be used. One option involves fusing the bones of the joint together.

This, however, will limit movement. Another option is to remove part of the joint and reconstruct it using either a tendon graft or an artificial substance. You and your physician will discuss the options and select the one that is best for you.

After surgery, you will have to wear a cast for several weeks. A rehabilitation program, often involving a physical therapist, helps you regain movement and strength in the hand. You may feel some discomfort during the initial stages of the rehabilitation program, but this will diminish over time.

Full recovery from surgery takes several months. Most patients are able to resume normal activities and are quite satisfied with the results.

The result of our OPEN MRI is a sophisticated diagnostic picture of the area your orthopedic specialist wishes to view. What’s more, there is no pain, no known side effects, and no radiation used with our OPEN MRI.

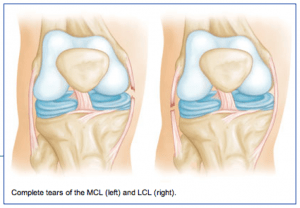

The result of our OPEN MRI is a sophisticated diagnostic picture of the area your orthopedic specialist wishes to view. What’s more, there is no pain, no known side effects, and no radiation used with our OPEN MRI.  The medial collateral ligament (MCL) runs from the inner side (medial side) of the femur (thigh bone) to the inner (medial side) of the tibia (lower leg bone). It prevents the knee from opening on the inside when struck from the outside of the knee joint. The MCL lies on the outside of the joint capsule and has a good blood supply that contributes to its good healing potential.

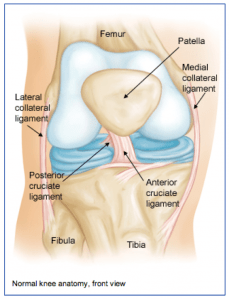

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) runs from the inner side (medial side) of the femur (thigh bone) to the inner (medial side) of the tibia (lower leg bone). It prevents the knee from opening on the inside when struck from the outside of the knee joint. The MCL lies on the outside of the joint capsule and has a good blood supply that contributes to its good healing potential.  The knee joint is one of the largest joints in the body. It is a complex joint with four bones: the femur (thigh bone), the tibia (main lower leg bone), the fibula (smaller lower leg bone), and the patella (kneecap). The bones are connected with four main ligaments: ACL (anterior cruciate ligament), PCL (posterior cruciate ligament), MCL (medial collateral ligament), and the LCL (lateral collateral ligament).

The knee joint is one of the largest joints in the body. It is a complex joint with four bones: the femur (thigh bone), the tibia (main lower leg bone), the fibula (smaller lower leg bone), and the patella (kneecap). The bones are connected with four main ligaments: ACL (anterior cruciate ligament), PCL (posterior cruciate ligament), MCL (medial collateral ligament), and the LCL (lateral collateral ligament).